Alligator On The Loose. Again.

Yet another alligator has been spotted in Pennsylvania. (Alligators are not native to Pennsylvania.)

You’ve probably heard this one before.

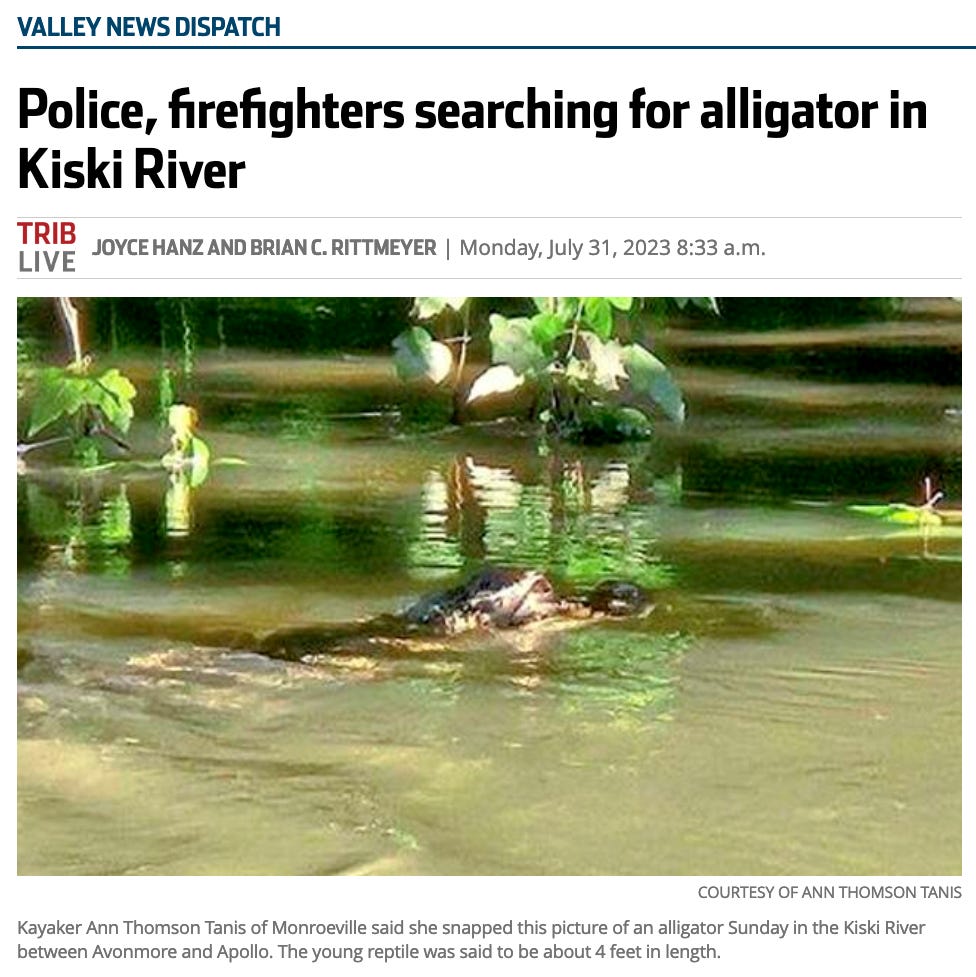

A four-foot-long alligator has been spotted in a Western Pennsylvania river. Reminder: Alligators are not native to Pennsylvania.

Amazingly, this isn’t even the first alligator spotted in Pennsylvania this year. In April, wastewater treatment plant owners found a small alligator outside of Lehigh. And just a few days ago, a landscaping crew discoverd another tiny gator while they were working in Exeter.

In fact, 22 alligators have been found roaming the Keystone State’s waterways since 2003. Which begs the question, where the cuss are all these tropical reptiles coming from?

They’re pets, of course—either escaped or intentionally released.

"New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Ohio all have laws banning the purchase of alligators pets," Jesse Rothacker, founder of the Forgotten Friend Reptile Sanctuary, told the York Daily Record’s Sam Ruland in 2018. "But Pennsylvania is one of the only states in the country where we have no laws, no background checks, no micro-chipping, no permits — no anything — preventing someone with about $50 from bringing home a pet alligator.”

Having an alligator is so common, apparently, the Valley News Dispatch’s Joyce Hanz scored an interview with a guy who lives near the Kiski River who currently owns 11 alligators. If you’re wondering, he keeps them in kiddie pools covered with chicken wire in what appears to be his living room, because why not I guess.

The gator wasn’t his, says 11-gator-dude.

Nor does it appear to belong to any of the other known alligator owners in the area. Because in this township of 4,604 people, there are apparently multiple people who own alligators.

“Not A Threat”

While I’m in love with the context provided in Hanz’s article—so, so many amazing details—there’s always one piece of this story that doesn’t get told accurately. And the problem with that is reflected in this quote from someone who lives near the latest gator sighting:

“I heard about it, and I’m not going back in the Kiski. I’ll find another river. I worry it would bite me,” said Jennifer Brow, who is described as an avid kayaker. “I want to keep all my limbs.”

Makes sense, right? No one wants to mess with a four-foot-long predatory reptile.

Of course, as a guy writing a book about North American wildlife, you know I had to reach out to an actual alligator expert to see just how dangerous this gator might be.

“A 4 ft. gator has a mouth that's about 6-7 inches long. So yeah, not very big,” says Adam Rosenblatt, an ecologist and alligator expert at University of North Florida. “A 4 ft. alligator is certainly not a threat to an adult human, and very unlikely to be a threat even to a small child. At that size they're mostly eating small fish, amphibians, crustaceans, and insects.”

So how big does a gator need to be to do some damage?

“Gators are generally not threatening to humans until they reach 6-7 ft. long, and even at that size they don't see adults as prey. But gators of that size can view small children as prey in rare cases,” he says. “For example, the 2-yeard old boy who was killed at Disney World back in 2016 was reportedly killed by a 7 ft. gator.”

(Sidenote: If you’re ever wondering how to talk to your kiddos about those kinds of rare, wildlife-human tragedies, I’ve got you covered: “Animal attacks are scary. Here's how to talk to kids about them.”)

Not that people shouldn’t be wary, of course. Wild animals are unpredictable and should be treated with a healthy respect in all instances.

“Injuries to people occur usually when gators are defending themselves because they feel threatened in some way, when they've previously been fed by people, or when they go after people's pets and the owners try to fight back,” says Rosenblatt.

It’s just, as humans, we’re notoriously bad at two things: estimating the size of wild animals—we always report that they’re bigger than they are—and gauging the threat posed by wildlife.

We either don’t give them enough respect, as evidenced by yet another tourist gored by a bison in Yellowstone, or we blow the threat level way out of proportion, as we’ve done with sharks, “murder hornets”, and literally any snake that has the audacity to just, you know, exist.

Pet Gators. Maybe Don’t?

In case it wasn’t abundantly clear where I stand on the topic of pet alligators—both inside their native range and out—I put the question to Rosenblatt. His response was unequivocal.

“People definitely should not keep gators as pets,” he says.

“They're cute and easy to handle when they're small, but they grow quickly and can cause injuries if owners don't know what they're doing. People also often don't feed pet alligators the right kinds of food and they can end up with health problems.”

Oh, and one last thing. If you already have an alligator, and you’re thinking about releasing it into the wild so that it can be free, you should know that—in Pennsylvania, at least—you’d be sentencing that animal to death.

Assuming someone doesn’t shoot it—which lots of people online are saying they want to do to the Kiski gator—or the local authorities don’t catch it, after wasting a lot of time and money, that gator is probably going to die come winter.

This is because even though some gators can survive brief periods of cold, via a process known as brumation, none seem to be able to survive the full extent of a northern winter.

“That's why their range is limited at North Carolina,” says Rosenblatt.