Need an attitude adjustment? Go hunting for shark teeth.

You can't hold eternity in your hand, but shark teeth'll get you close.

Did you know there are places on this planet where you can stroll along a beach and pluck pieces of extinct sharks out of the surf?

And not, like, remote or exotic places, such as the windswept shores of Antarctica. I just did this in Maryland. About thirty minutes away from the nearest Taco Bell.

Now, you’re probably thinking, sure, but who has the particular paleontological expertise to be able to identify fossils? Not me, that’s for dang sure. Nor do I possess any fancy excavating equipment or experience. (I’ve interviewed lots of experts who have such things, but it ain’t me, babe.)

Now here’s the cool part, and the part that continues to blow my mind:

Between 59 to 55.5 million years ago, there were so many goldarned sharks swimming through the earth’s oceans, each of them constantly replacing their chompers—as modern sharks continue to do—and so many of those teeth got buried in sediments and preserved over the eons that some places just have these things lying around at low-tide on any given day. And even though expert fossil hunters and tourists like myself go to these places basically all the time and take home what they find, there are still more fossilized shark teeth to be found the next day, and the next day, and the next day.

The human brain is not built to comprehend just how many sharks there would have had to have been to create this everlasting supply of wonder. Nor can I tell you how many sharks would have lived and died over the 4.5 million years represented by the deposits eroding out of Maryland’s Purse State Park cliffs (which is where my family and I ventured recently).

All I can tell you is this: I went there hoping I’d find enough fossils that each of my three kids would have a single tooth to take home. But this is how many shark teeth we found in about three hours of goofing around.

I got 99 shark teeth, but the Meg ain’t one

If the picture above isn’t the most bonkers thing you’ve seen in a long while, then you’re living a blessed life. Because I am still in shock that we were able to leave with such a haul.

But it’s not just that. It’s that these creatures were alive dozens of millions of years ago. These were living things, the ancestors of today’s goblin sharks, sand tiger sharks, and mackerel sharks. One may even have come from the great grandmama of the Megalodon, known as Otodus. (Again, I’m not an expert on any of this, so I’m leaning on the identifications done by FossilGuy.com.)

Truth be told, we had really hoped to find a Megalodon tooth. Because they can be like the size of your palm. And who doesn’t love those awful Jason Statham movies? Alas, the Purse State Park site, which is on the banks of the Potomac River, is too old for Meg teeth, and the other, younger site we visited—Calvert Cliffs State Park, which is on the Chesapeake Bay—was already well picked over.

But even though the teeth we found were mostly no bigger than a candy corn, each represents a totally ridiculous series of events.

Each tooth belongs to a species that no longer exists on this planet. In many cases, teeth like these are the only evidence that these things ever existed at all.

As if that weren’t enough, each tooth would have been just one of the tens of thousands of teeth that that shark would have created and discharged over the course of its life. (Lemon sharks are estimated to go through around 30,000 teeth from birth to death, as my colleague Melissa Cristina Márquez once reported.) And each would have had to have gotten lucky enough to fossilize, rather than decay and disappear.

To explain that a bit, let’s hear from Dr. Anne Marie Helmenstine over at ThoughtCo.

Shark teeth are made up of calcium phosphate, which is the mineral apatite. Although shark teeth are sturdier than the cartilage that makes up their skeleton, the teeth still disintegrate over time unless they are fossilized. This is why you rarely find white shark teeth on a beach.

Shark teeth are preserved if the tooth is buried, which prevents decomposition by oxygen and bacteria. Shark teeth buried in sediments absorb surrounding minerals, turning them from a normal whitish tooth color to a deeper color, usually black, gray, or tan. The fossilization process takes at least 10,000 years, although some fossil shark's teeth are millions of years old! Fossils are old, but you can't tell the approximate age of a shark tooth simply by its color because the color (black, gray, brown) depends completely on the chemical composition of the sediment that replaced the calcium during the fossilization process.

🎶Oceans rise, empires fall🎶

Yes, my kids have been listening to the Hamilton soundtrack all summer and my brain’s synapses are wired with historical raps, but there’s another thing these shark teeth have me thinking about. And that’s time.

In my last post, I talked about how spotted salamanders come to the surface for just a few days each year, and that the hour they choose is often one we humans describe as The Literal Worst—early spring, when all of Pennsylvania is mud-brown and seemingly lifeless. But to the salamanders, that moment is the only world they want or need.

Now, holding a pile of teeth only slightly younger than the last dinosaurs, I’m thinking about the nature of impermanence. How, even when everything around us seems so overwhelmingly heavy, all of this is just a blip in the history of this world. How each atrocity, each injustice, each disaster is just a notch on a timeline that stretches back past mass extinctions that nearly wiped out all life on this planet, not once, but five separate times.

How even these ancient teeth are relative babies compared to, oh say, the youngest rocks in the Grand Canyon (which are 270 million years old). Or how a meteorite from outer space just crashed into a house in Georgia and scientists think it’s older than Earth itself.

Not that contextualizing our existence as little or fleeting is an excuse to litter or be a jerk to service industry workers, but it does feel like an opportunity to take a deep breath. Maybe even a shower. And to remember that whatever is weighing you down right now with what feels like geologic force is probably not as powerful or as permanent as it seems.

The Megalodon was the biggest, baddest shark to ever exist, and it existed with a vengeance for 20 million years. And yet… these days, all we have to remember it by are fossilized teeth, a few vertebrae, and some scales. That means that the beast Statham fights against in his movies and the depictions you’ve seen in other media are best-guesses, approximations, or fanciful re-imaginings. We don’t actually know what this giant megabeast looked like, despite it being on this planet more than 66 times longer than us. (I wrote about this for Nat Geo not long ago, by the way.)

By all means, keep donating to causes you care about, voting for politicians who might actually make the world a better place, and doing all those little acts of kindness and resistance that make life worth living.

But also remember that one day—a lot sooner than you think—all of your teeth will fall out of your head and your body will disintegrate, and unless some of it gets trapped in sediment and turned to stone, everything you are will revert to cosmic dust and get swept back up into the cycle of atoms that makes the universe go round.

We’d be extraordinarily lucky to have a body part lapped up onto a beach somewhere 55 million years into the future. Even bodies treated with modern embalming methods are unlikely to last more than 50 years. More likely, it’s poof, and you’re gone, like a dandelion met with the breath of a child.

This world is beautiful and terrible, impossibly old and continuously new. And if the long march of life before us is any indicator, it’s ours for only the briefest of moments. And yet how much of our limited time here is spent on cruelty, how much on boredom?

How little on wonder?

Oh, by the way

That book… you know the one I first started circling nearly ten years ago? The one I started this newsletter for? The one I’ve probably cornered you about at a bar, family reunion, or soccer sideline?

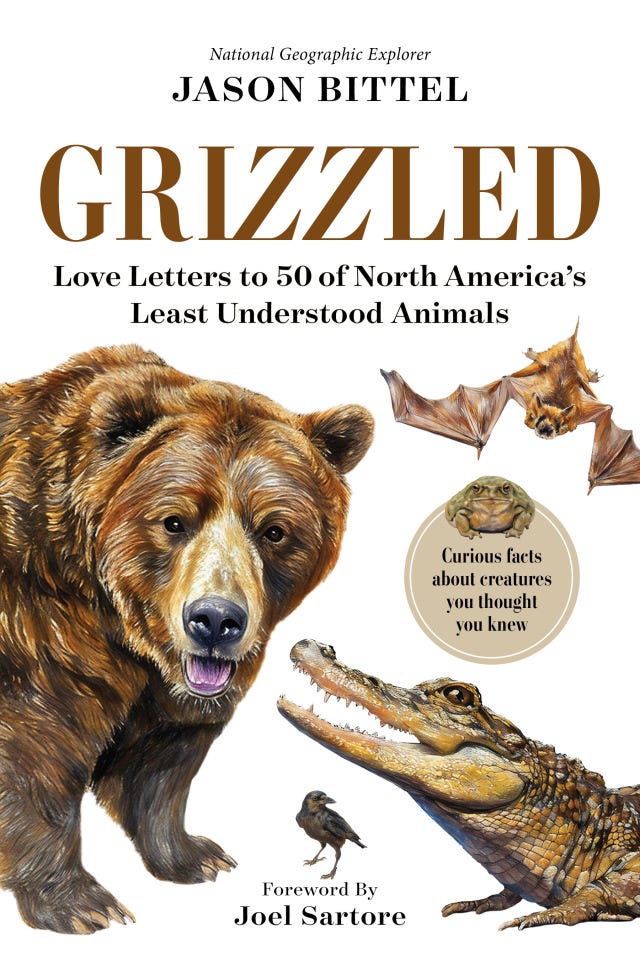

Yeah, it’s got a new name, new art style, new foreword from Joel Sartore(!!!), and a new publication date. On March 3, 2026… We ride.