The Worst Thing You Can Do For Deer

The road to hell is paved with good intentions. Deer hell, at least.

It’s freezing this morning where I live in southwestern Pennsylvania, and the world looks brown and dead. But while black bears hibernate and migratory birds enjoy the warmth of the tropical sun, white-tailed deer are just out there, walking around, and doing the best they can with what they’ve got. Some of them even have ribs poking through their gray winter coats.

And that doesn’t sit well with a lot of people. But before you go ordering a sack of corn from Amazon, you might want to learn a thing or two about deer guts.

In fact, reading this email might just save a deer’s life.

But before we get into fun stuff like rumen acidosis, I’d like to welcome all of our new subscribers to the SORT OF FUNNY FIELD GUIDES email! A lot of you are coming from Twitter, where I recently posted a thread about moose antlers! (Conversely, if you missed all that antler-y goodness, just click on the tweet below and you’ll be able to see the whole thread. You can also read my story for National Geographic News that inspired the thread: “Why moose need to shed their antlers”)

Anyway, if you’re new here, we’ve been doing a bit of a deep dive on deer. For one, I’ve got a chapter about them in my upcoming book, but two, there are TONS OF COOL THINGS I couldn’t fit into that chapter. So I’m giving them to you here, for freesies.

To get caught up on the Deer Series: In Part 1, we learned about some of the white-tailed deer’s super senses, including its panoramic vision and muscley ears. Part 2 was dedicated to the deer’s sniffer, as well as the invisible ink that is deer urine. And Part 3 delved into deer hanky panky, the myth behind big bucks, and generally, what Bambi got wrong. Part 4 covered the time I helped raise a baby deer, or fawn, and why that was actually the exact opposite of what you should do.

Now, for Part 5, we’re going to dive into the deer’s digestive tract, Magic School Bus-style. So buckle up.

Feeding Deer Is Bad For Deer

I know, that is going to sound counterintuitive. So let’s break it down like a complex carbohydrate in a ruminant’s multi-chambered stomach—an analogy that will make a lot more sense in a minute!

For starters, putting out corn, apples, or other foods teaches deer to associate humans with food. While this might seem harmless, it can make the animals more likely to get hit by a vehicle or get into an altercation with a family pet or child. Deer appear peaceful, but they are wild animals that can become aggressive at a moment’s notice.

Interestingly, feeding deer can lead to their demise in another way.

For millions of years, cervids (deer, elk, moose, etc) have relied on the bounty of the wilderness for their survival. But what’s available in the supermarket of the wild changes with the seasons and habitat. Fresh plant shoots and buds sprout in the spring, summer offers juicy berries, and fall boasts ripened apples and acorns. This is a vast oversimplification, of course, and deer count hundreds of different plants, animals, and even fungi among their typical diets.

The catch is, while deer eat lots of different foodstuffs, they can’t eat them all the time. Deer are ruminants, which means they have multi-chambered stomachs that require they cough up and chew their food (cud) more than once. It sounds a little gross, but this apparatus allows ruminants to eke nourishment out of foods that would kill a tiger, shark, or human.

A deer can tear up complex carbohydrates, like the cellulose found in leaves, and turn them into energy. Separate chambers in the stomach allow for forage to break down into simple sugars which are in turn converted into volatile fatty acids that the rumen walls are able to absorb.

However, none of this would be possible without bacteria!

Microbes not only assist the gut in breaking food down, but they also produce proteins and amino acids that supplement what the deer gets from its daily food intake. The deer’s digestive tract can also create potassium and vitamin B, meaning they don’t need to worry about getting such nutrients from the wild. Frankly, the ruminant way of life is akin to alchemy.

It does have a weakness, though. Because so much of the deer’s digestion relies on its stowaway stomach microbes, the animals must change their diet slowly. Normally, this is fine, because the seasons take their time. But a well-meaning human can mess it up right quick by feeding deer dried corn in the middle of winter.

Rumen Acidosis—The Winter Killer

You might think you’re helping a deer by giving it a little extra food when the world is barren and bleak. But you’re forgetting that deer are built for bootstrapping it.

During winter, a white-tailed deer can go a solid month without eating. It may lose up to 20 percent or more of its body weight.

As the seasons change, so too does the deer’s body. Inside the rumen’s walls, tiny, finger-like projections called papillae swell, shrink, elongate, and multiply depending on what foods the deer chooses. Saliva production ramps up to wash down extra-fibrous meals, like twigs and bark, since they might be the only edible materials for miles around. The deer’s stomachs will also expand in size so that they can take account for the need for greater quantities of lower quality food.

And throughout it all, the deer’s microbe community adapts, with different species proliferating at different times to make use of different foods.

In general, deer eat diets that are heavy in fiber and light on carbohydrates. This is especially true in winter, when the animals survive almost exclusively on woody twigs, branches, and other fibrous materials. But most of the foods people like to give deer in the winter—corn, wheat, barley, and other grains—are carbohydrate rich.

A bellyful of corn triggers a boom in the deer’s carbohydrate-munching bacteria. All these new, carbohydrate crunchers churn out large quantities of lactic acid, which alter the rumen’s pH level to the point where other microbes can’t survive. At the same time, a dangerous feedback cycle starts where the acid causes inflammation of the gut and slows down its inner workings, causing food to become trapped inside. The deer’s body diverts water to the rumen in an attempt to address the issue, but this just dehydrates the animal. Finally, the body begins to absorb all of that lactic acid and moves it into the bloodstream where it can poison the deer.

This is what’s known as rumen acidosis. It can kill a deer within 72 hours—a death sentence so fast, the animals appear to be completely healthy, despite an enlarged and inflamed gut. Deer that survive may still suffer lifelong effects of a damaged rumen.

Still thinking about feeding deer? Really?

Okay, well, you should know that supplemental food sources make deer congregate in unnatural numbers. And this makes it more likely for them to pass diseases and parasites onto one another.

In recent years, researchers in the United States and Canada have become increasingly concerned about a prion disease spreading throughout the continent’s cervids. Chronic Wasting Disease, or CWD for short, is what’s known as a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy. In other words, it’s a disease that attacks the brain, similar to the one that caused Mad Cow Disease among cattle in the United Kingdom in the 1990s.

Unfortunately for deer, CWD is 100 percent fatal. And it’s spread through saliva, blood, urine, and feces—most of which deer are more likely to come in contact with if they’re all herded around the same feeding site. At the time of this writing, CWD has been found in 30 states and four Canadian provinces, as well as in Norway, Finland and South Korea.

The good news is CWD has not been shown to leap into humans, even those who eat deer meat, but scientists are nevertheless worried about the possibility. (I wrote about this for The Washington Post, if you’re interested in learning more.)

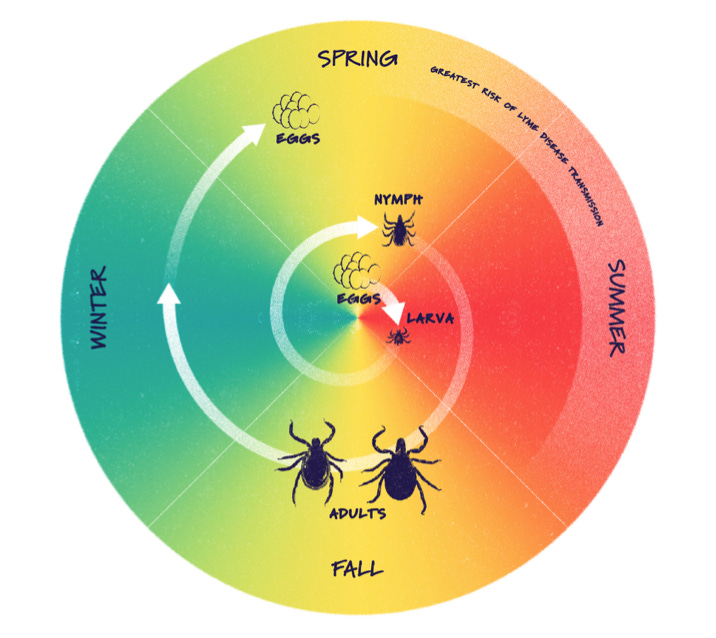

One pathogen we do know deer can spread to humans is Lyme disease, by way of the black-legged tick. This is because deer play hosts to many different species of tick, including some that carry viruses and bacteria that can infect humans. And if there are deer in your backyard noshing at the corn trough, then you better believe there will be more ticks of various life stages waiting to crawl up your pant legs.

In short, the best way to live with deer is to enjoy them from a distance. Don’t try to feed them, cuddle them, or let your pets near them. Deer are wild animals with millions of years of survival experience on their resumes.

The only thing deer truly need from us is space.