Hello, remember me? I know, it’s been awhile!

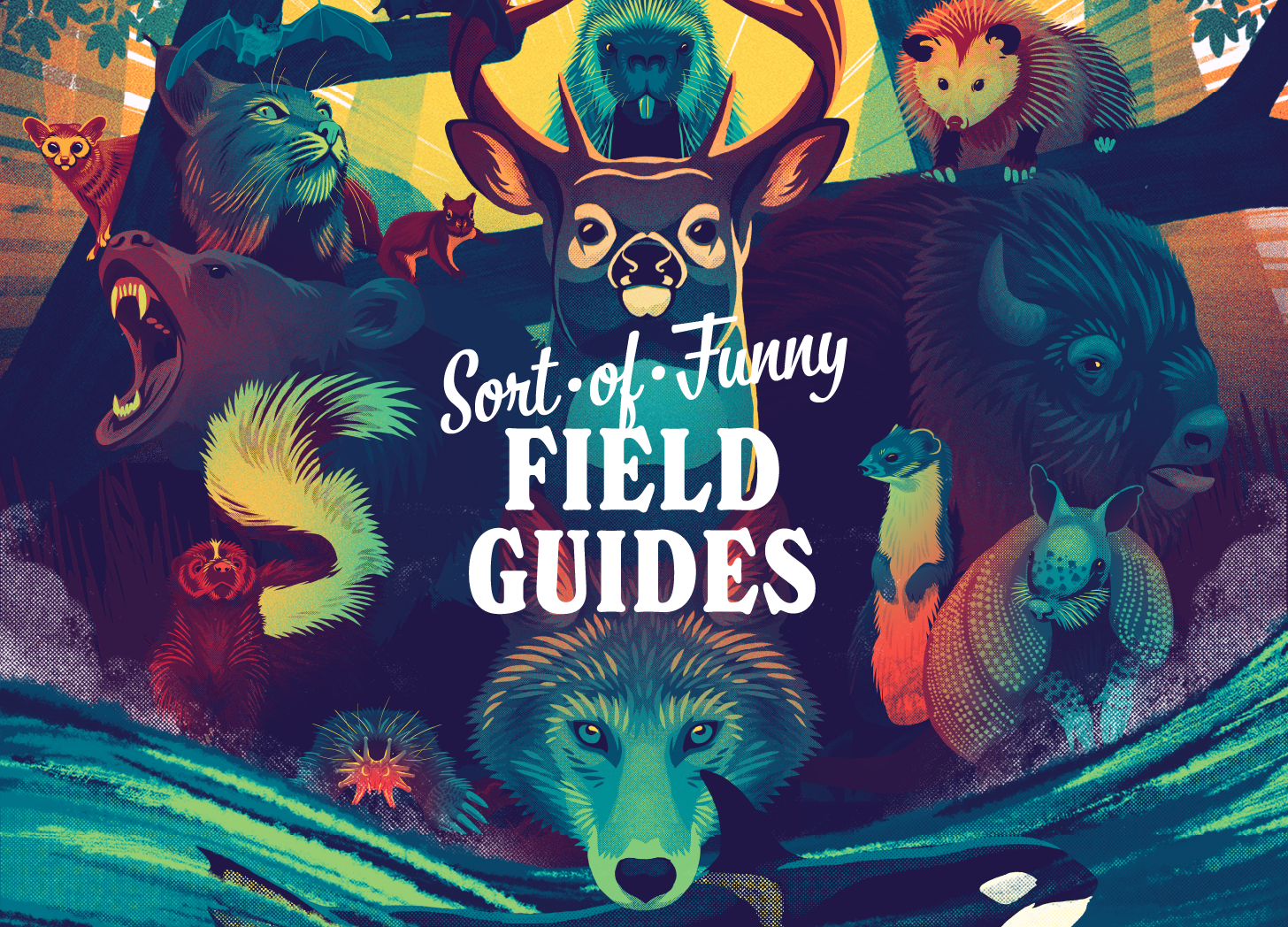

But there’s a good reason for that: I’m VERY CLOSE to completing the draft of my book! You may remember that it’s tentatively titled Sort Of Funny Guides: North American Wildlife, and is due to be published by National Geographic Books in spring of 2025. (The name could still change, but that’s the gist.) And unlike the kids’ books I’ve published, this one will be geared toward teens and adults. In other words, it’s for all of you! Here’s a little graphic inspiration.

I truly cannot wait to get this baby out into the world and into your hands. It will have quotes from dozens and dozens of awesome and hilarious and incredibly smart scientists and experts. It will feature 50 chapters about all sorts of critters, from the American buffalo and California condor to the blue crab, white-tailed deer, and yellowjacket. It will leap off the page with beautiful illustrations and evocative, down-to-earth language that will let literally anyone pick the thing up and learn about science in a way that won’t put you to sleep but will have you talking about jellyfish reproduction and star-nosed mole brain maps on the sidelines of your kids’ soccer game. (Okay, maybe I’m projecting a little hard here.)

Anyway, I really think you’re going to love it. Because if you love learning about animals as much as I do, then your mind might just explode when you realize how much you don’t know about the hairy, scary, scaly, and extraordinary living things scuttling all around us.

And that brings us to the topic of today’s newsletter—the mother-cussin’ mountain beaver.

Can I just just come right out and tell you that I did not know mountain beavers existed? Like, sure, I knew beavers existed—I just wrote a whole chapter about the buck-tooths. But “mountain beavers” are not true beavers.

They’re, well, whatever this thing is.

Now look, I’m a guy who writes about animals for a dang living. I read studies for breakfast and spend more time with scientists on Zoom than I do with best friends who live in other states. And sometimes all of that can create a feeling of having seen it all when it comes to the natural world.

But I can also tell you that, oh, probably about once a week, a new observation or study comes out that takes that smugness, folds it in half twelve times, and tosses it out the ever-lovin’ window. Because I am constantly being reminded that we are, literally every day, learning new and amazing stuff about animals on this planet.

That realization is both humbling and all kinds of exhilarating. (It also means job security for a guy who likes to keep dead spiders and porcupine skulls on his desk and bobcat urine in the beer fridge.)

So, now that you’ve remembered that you subscribe to this intermittent newsletter, would you like to get to know the animal that Ben Goldfarb (author of Eager: The Surprising Secret Lives of Beavers and Why They Matter) described as “an odd rodent, only distantly related to [true beavers], with the peaked face of a mole and the long, grotesque fingers of Mr. Burns”?

Mountain Beavers, We Hardly Know Ye

Okay, let’s start with the basics.

Mountain beavers (Aplodontia rufa) are rodents, as are true beavers, of which there are two species—North American beavers (Castor canadensis) and Eurasian beavers (Castor fiber). But that’s pretty much where the similarities end, because as Goldfarb said, mountain beavers are not particularly closely related to true beavers.

Where true beavers have giant, scaly paddles for a tail, mountain beavers have small, furry nubs. Even with the sizeable chompers that grace pretty much all the rodents, mountain beavers don’t chew down trees. (Of some interest is the fact that mountain beavers are considered to be the most primitive of all rodents, due mostly to the way their mouth muscles connect to their skull. In any event, the species isn’t thought to have changed much since the Miocene Period, or at least five million years ago.)

Mountain beavers also do not build dams. Nor do they live in water, though they are capable swimmers. Rather, mountain beavers use those gnarly claws to dig burrows into the earth that can extend as far as a football field. And within these networks, you will find rooms that mountain beavers use for specific purposes.

There are mountain beaver potties, mountain beaver pantries, mountain beaver snuggle areas, mountain beaver dumps, and mountain beaver mystery rooms. The latter of which consist of big clumps of dirt and rocks that scientists don’t have a great explanation for. These so-called “earth ball” chambers might be used as material that can block other entrances or exits, or maybe even as sharpening material for the mountain beaver’s teeth. Who the heck knows.

Perhaps the funniest thing about my so-called mountain beavers? They don’t actually live on mountains! Rather, the critters prefer lower elevation areas from southern British Columbia to California.

Sometimes people call the mountain beavers other names, such as boomer, sewellel, whistler, chehalis, and mountain rat—all of which are frankly probably better than “mountain beaver” given all the things you now know about mountain beavers.

There’s probably a great deal more to say about this species, but to be honest, you have better things to do, so let’s cut to the best part—the mountain beaver’s gigantic parasites.

Fleas Of Unusual Size

Most people with pets have probably seen a flea or two in their lifetimes. They’re tiny, powerfully-jumpy insects that live on other animals and suck their blood.

Fleas, the animal, are not to be confused with Flea, the musician. (Though, in other insect news, the rarely-shirted bassist for the Red Hot Chili Peppers does apparently keep his own bees. Yes, Flea has bees.)

The thing about fleas is they’re teeny-tiny. Usually, you need a microscope to even see the buggers clearly. But there are also like 2,500 different kinds of fleas, some of which only seem to prey upon a single host species.

And the species that preys upon mountain beavers is commonly believed to be the largest flea species on Planet Earth.

It’s known as Hystrichopsylla schefferi, and it is a whopper.

So, how big can a mountain beaver flea possibly be? Well, these blood-sucking babies can grow to lengths of more than half an inch. That means we’re talking about a flea the size of a garlic clove. A flea big enough to get caught in your throat.

In fact, here’s a picture of a mountain beaver flea next to a run-of-the-mill cat flea. Because some things you just have to see to believe.

Unbelievably, giving how conspicuous these creatures must be, no living expert had ever laid eyes upon a living specimen of mountain beaver flea until a husband-and-wife, scientist-and-science-journalist duo set out to literally dig a mountain beaver out of its den (which is legal, by the way) and then document the mini-monsters crawling all over its pelt for Western Washington University.

And then, probably no one would have even known about that if the latter of the two—Carol Kaesuk Yoon—didn’t write this fantastic and hilarious story about the ordeal for The New York Times.

Friends, I can’t recommend this story enough. Here’s Yoon writing about how one collects fleas of unusual size:

“The device hanging from my lips was an aspirator. It had a plastic vial stoppered by a rubber plug through which were threaded two thin metal tubes, with small rubber hoses attached. The end of one hose in my mouth, I held the tip of the other over the flea, where it lay amid mountain beaver fur. One quick gasp, and the bug would end up — ping! — in the vial.

I tried not to think of all the micro-organisms and parasites I would be inhaling. I breathed in as sharply and deeply as I could. Nothing doing. The world’s largest flea moved about a quarter-inch into the rubber tubing as my agitated husband, still grasping the mountain beaver, shouted, “Suck! Suck harder!”

This is an unaccountably rude-sounding thing to have yelled at you. Still, several increasingly asthmatic, panicked inhalations later, the flea was in the vial.”

Amazing.

So, uh, how many of you would breathe-collect a giant flea from a wet, angry rodent that looks like this?

Chimpanzee Menopause

In absolutely unrelated news, scientists have just discovered that one very special population of chimpanzees in Uganda show all the signs of undergoing menopause, marking the first time such a thing has been documented in another primate beside humans.

It is not an exaggeration to say that chimpanzee menopause is a really, really big deal in the scientific world. And I got to write about it for National Geographic.

Enjoy!